A vaccination against tuberculosis (TB) could be made more effective by injecting it directly into the bloodstream at a higher dose, new research suggests.

TB, caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is one of the leading causes of infection globally, killing approximately 1.7 million people and infecting around 10 million annually. So far, the only licensed vaccine to fight this disease is the bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine, containing a weakened form of TB found in cattle. This vaccine is normally given to infants by injecting under the skin, or intradermally, to protect them against various types of TB. However, it isn’t very effective at protecting adults and adolescents from pulmonary TB, the most common type which affects the lungs.

Now, work by researchers at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) has demonstrated that introducing the BCG vaccine intravenously (IV) results in a greatly improved immune response against TB, and a grants a much higher degree of protection.

A major challenge in producing an effective vaccine against TB is making sure that it generates both a high and long-lasting T-cell response in the lungs. T-cells are a vital part of the immune system and are needed to control the response to invading pathogens – but introducing the BCG vaccine under the skin doesn’t result in a high enough T-cell count in the lungs to fight TB. What’s more, what T-cells are produced don’t usually stay around long enough to be effective.

The researchers at NIAID aimed to test whether changing the way the BCG vaccine is introduced can improve T-cell immunity and increase protection against TB infection.

To achieve this, they vaccinated rhesus macaque monkeys with BCG either as ID at a normal dose; as IV, ID or inhaled mist at a higher dose; or as a combination of ID and mist at a normal dose. They then waited six months, then infected the monkeys with TB to test the efficacy of each method. Another group was left unvaccinated as a control for the test.

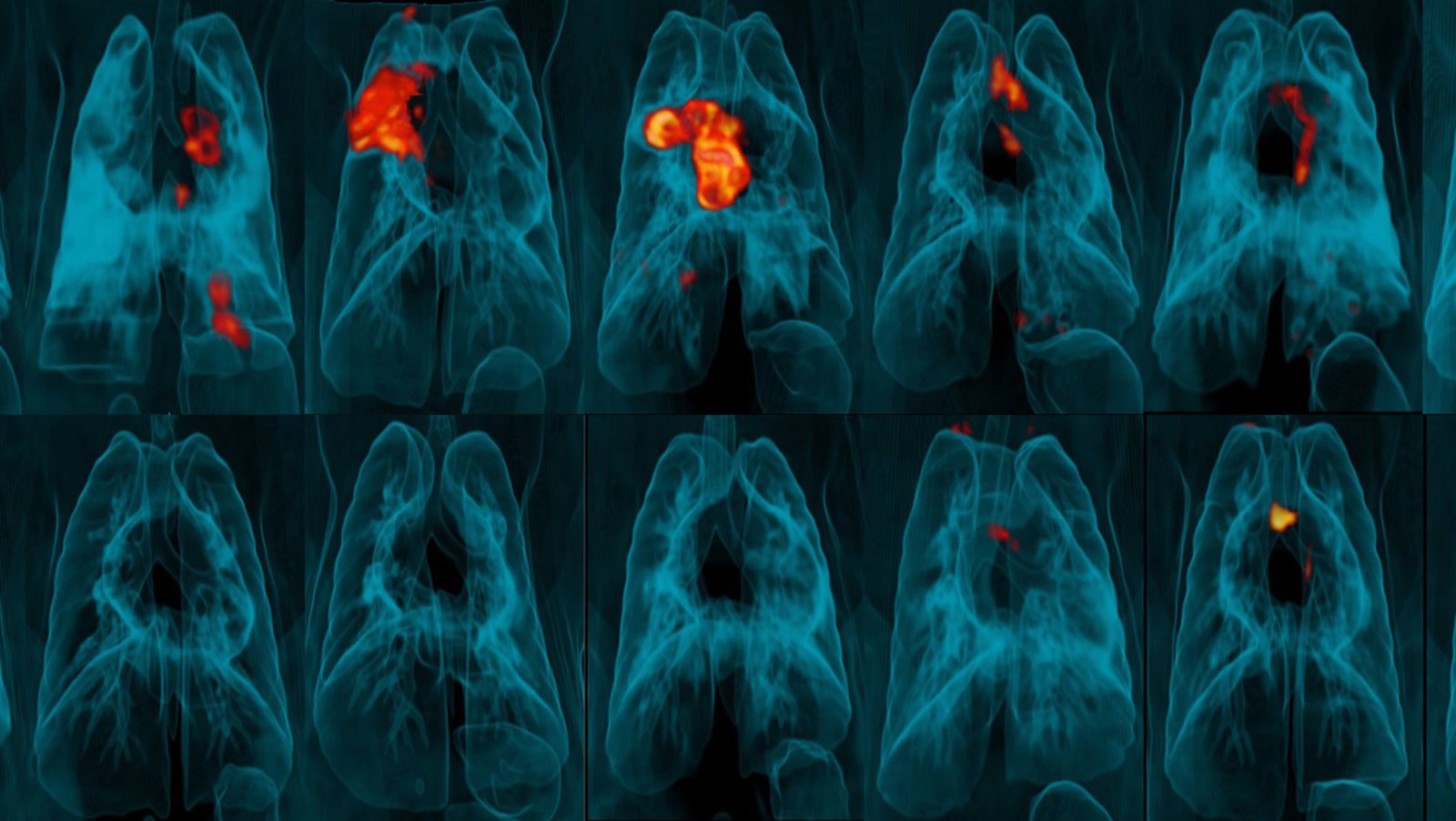

They found that the monkeys who had received the IV vaccine were the most protected against TB, with 90% exhibiting no significant signs of infection or disease. By contrast, all other macaques showed a much-reduced level of protection. Seven of the eight monkeys who received a high dose ID vaccine went on to develop infection.

The T-cell data of the IV group was also telling, with only these macaques showing a significantly increased T-cell level, which was sustained in their lungs for up to six months.

So why could a vaccine which is introduced via IV result in better protection? According to senior author Professor JoAnne Flynn, from the Pitt Center for Vaccine Research, this could be because this route speeds up the vaccine’s beneficial effects.

“The reason the intravenous route is so effective is that the vaccine travels quickly through the bloodstream to the lungs, the lymph nodes and the spleen,” Professor Flynn explains, “and it primes the T-cells before it gets killed.”

While this work is promising, further work still needs to be done to ensure that this method of delivery would be safe in humans.

The paper concludes by stating that the study supports the clinical development of an IV BCG vaccine against TB in adults and adolescents, and that an IV route might similarly improve the efficacy and protection granted by other types of vaccines.